The Revolutions of 1989, also known as the Fall of Communism, was a

revolutionary wave

A revolutionary wave or revolutionary decade is one series of revolutions occurring in various locations within a similar time-span. In many cases, past revolutions and revolutionary waves have inspired current ones, or an initial revolution has ...

that resulted in the end of most

communist states

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by Marxism–Leninism. Marxism–Leninism was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Comint ...

in the world. Sometimes this revolutionary wave is also called the Fall of Nations or the Autumn of Nations,

a play on the term

Spring of Nations

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

that is sometimes used to describe the

Revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

in Europe. It also led to the eventual breakup of the

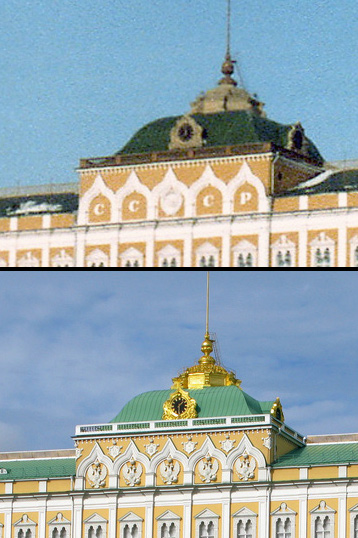

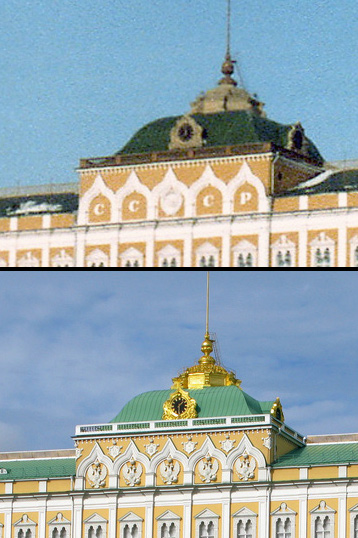

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

—the world's largest communist state—and the abandonment of communist regimes in many parts of the world, some of which were violently overthrown. The events, especially the fall of the Soviet Union, drastically altered the world's

balance of power, marking the end of the

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

and the beginning of the

post-Cold War era.

The earliest recorded protests were started in

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

, then part of the Soviet Union, in 1986 with the

student demonstrations — the last chapter of these revolutions is considered to be in 1993 when

Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailand t ...

enacted a new Constitution in which communism was abandoned. The main region of these revolutions was in Eastern Europe, starting in

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

with the Polish workers' mass strike movement in 1988, and the revolutionary trend continued in

Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

,

East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

,

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

,

Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

and

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

. On 4 June 1989, the trade union

Solidarity won an overwhelming victory in a

partially free election in Poland, leading to the peaceful

fall of communism in that country. Also in June 1989,

Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

began dismantling its section of the physical

Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. The term symbolizes the efforts by the Soviet Union (USSR) to block itself and its s ...

, while the opening of a border gate between

Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

and Hungary in August 1989 set in motion a peaceful chain reaction, in which the

Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

had disintegrated. This led to

mass demonstrations in the cities such as

Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as wel ...

and subsequently to the

fall of the Berlin Wall

The fall of the Berlin Wall (german: Mauerfall) on 9 November 1989, during the Peaceful Revolution, was a pivotal event in world history which marked the destruction of the Berlin Wall and the figurative Iron Curtain and one of the series of eve ...

in November 1989, which served as the symbolic gateway to the

German reunification

German reunification (german: link=no, Deutsche Wiedervereinigung) was the process of re-establishing Germany as a united and fully sovereign state, which took place between 2 May 1989 and 15 March 1991. The day of 3 October 1990 when the Ge ...

in 1990. One feature common to most of these developments was the extensive use of

campaigns of

civil resistance

Civil resistance is political action that relies on the use of nonviolent resistance by ordinary people to challenge a particular power, force, policy or regime. Civil resistance operates through appeals to the adversary, pressure and coercion: i ...

, demonstrating popular opposition to the continuation of

one-party rule

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other parties ...

and contributing to the pressure for change. Romania was the only country where

citizens and opposition forces used violence to overthrow its communist regime. The Cold War is considered to have "officially" ended on 3 December 1989 during the

Malta Summit between the Soviet and American leaders. However, many historians argue that the collapse of the Soviet Union on 26 December 1991 was the end of the Cold War.

The Soviet Union itself became a multi-party semi-presidential republic from March 1990 and held its first

presidential election

A presidential election is the election of any head of state whose official title is President.

Elections by country

Albania

The president of Albania is elected by the Assembly of Albania who are elected by the Albanian public.

Chile

The pre ...

, marking a drastic change as part of its

reform program. The Union

dissolved in December 1991, resulting in seven new countries which had declared their

independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

from the Soviet Union in the course of the year, while the

Baltic states

The Baltic states, et, Balti riigid or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term, which currently is used to group three countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, ...

regained their independence in September 1991 along with

Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

,

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

,

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of th ...

and

Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''Ox ...

. The rest of the Soviet Union, which constituted the bulk of the

area

Area is the quantity that expresses the extent of a region on the plane or on a curved surface. The area of a plane region or ''plane area'' refers to the area of a shape

A shape or figure is a graphics, graphical representation of an obje ...

, continued with the establishment of the

Russian Federation

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

.

Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and shares ...

and

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

abandoned communism between 1990 and 1992, and by the end Yugoslavia had

split into five new countries.

Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

dissolved three years after the

end of communist rule, splitting peacefully into the

Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The ...

and

Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

on 1 January 1993. North Korea has abandoned Marxism-Leninism since 1992.

The impact of these events were felt in many

third world

The term "Third World" arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Western European nations and their allies represented the " First ...

socialist states

Several past and present states have declared themselves socialist states or in the process of building socialism. The majority of self-declared socialist countries have been Marxist–Leninist or inspired by it, following the model of the Sovi ...

throughout the world. Concurrently with events in Poland,

protests in Tiananmen Square (April–June 1989) failed to stimulate major political changes in

Mainland China

"Mainland China" is a geopolitical term defined as the territory governed by the People's Republic of China (including islands like Hainan or Chongming), excluding dependent territories of the PRC, and other territories within Greater China. ...

, but

influential images of courageous defiance during that protest helped to precipitate events in other parts of the globe. Three Asian countries, namely

Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

,

Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailand t ...

and

Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million, ...

, had successfully abandoned communism by 1992–1993, either through reform or conflict. Additionally, eight countries in Africa or its environ had also abandoned it, namely

Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

,

Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

,

Benin

Benin ( , ; french: Bénin , ff, Benen), officially the Republic of Benin (french: République du Bénin), and formerly Dahomey, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Togo to the west, Nigeria to the east, Burkina Faso to the north ...

,

Congo-Brazzaville

The Republic of the Congo (french: République du Congo, ln, Republíki ya Kongó), also known as Congo-Brazzaville, the Congo Republic or simply either Congo or the Congo, is a country located in the western coast of Central Africa to the w ...

,

Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

,

Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constituti ...

, as well as

South Yemen (unified with

North Yemen

North Yemen may refer to:

* Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen (1918–1962)

* Yemen Arab Republic

The Yemen Arab Republic (YAR; ar, الجمهورية العربية اليمنية '), also known simply as North Yemen or Yemen (Sanaʽa), was a ...

).

The political

reforms

Reform ( lat, reformo) means the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The use of the word in this way emerges in the late 18th century and is believed to originate from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement ...

varied, but in only four countries were

communist parties

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ...

able to retain a monopoly on

power

Power most often refers to:

* Power (physics), meaning "rate of doing work"

** Engine power, the power put out by an engine

** Electric power

* Power (social and political), the ability to influence people or events

** Abusive power

Power may a ...

, namely China,

Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

,

Laos

Laos (, ''Lāo'' )), officially the Lao People's Democratic Republic ( Lao: ສາທາລະນະລັດ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ປະຊາຊົນລາວ, French: République démocratique populaire lao), is a socialist ...

, and

Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

. However, these countries would later make economic reforms in the coming years to adopt some forms of

market economy

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production and distribution to the consumers are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand, where all suppliers and consumers ...

under

market socialism

Market socialism is a type of economic system involving the public, cooperative, or social ownership of the means of production in the framework of a market economy, or one that contains a mix of worker-owned, nationalized, and privately owne ...

. The

European political landscape changed drastically, with several former Eastern Bloc countries joining

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

and the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

, resulting in stronger

economic

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

and

social integration

Social integration is the process during which newcomers or minorities are incorporated into the social structure of the host society.

Social integration, together with economic integration and identity integration, are three main dimensions of ...

with

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

and North America. Many communist and socialist

organisations

An organization or organisation (Commonwealth English; see spelling differences), is an entity—such as a company, an institution, or an association—comprising one or more people and having a particular purpose.

The word is derived from ...

in the

West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sunset, Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic languages, German ...

turned their guiding principles over to

social democracy

Social democracy is a Political philosophy, political, Social philosophy, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocati ...

and

democratic socialism

Democratic socialism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing political philosophy that supports political democracy and some form of a socially owned economy, with a particular emphasis on economic democracy, workplace democracy, and workers' self- ...

. In contrast, and somewhat later, in South America, a

Pink tide

The pink tide ( es, marea rosa, pt, onda rosa, french: marée rose), or the turn to the left ( es, giro a la izquierda, link=no, pt, volta à esquerda, link=no, french: tournant à gauche, link=no), is a political wave and perception of a tur ...

began in

Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

in 1999 and shaped politics in the other parts of the continent through the early 2000s. Meanwhile, in certain countries the aftermath of these revolutions resulted in conflict and wars, including various

post-Soviet conflicts

This article lists the post-Soviet conflicts; the violent political and ethnic conflicts in the countries of the Post-Soviet states, former Soviet Union following its Dissolution of the Soviet Union, dissolution in 1991.

Some of these conflicts ...

that remain frozen to this day as well as large-scale wars, most notably the

Yugoslav Wars

The Yugoslav Wars were a series of separate but related#Naimark, Naimark (2003), p. xvii. ethnic conflicts, wars of independence, and Insurgency, insurgencies that took place in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, SFR Yugoslavia from ...

which led to Europe's

first genocide since the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

in

1995

File:1995 Events Collage V2.png, From left, clockwise: O.J. Simpson is O. J. Simpson murder case, acquitted of the murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman from the 1994, year prior in "The Trial of the Century" in the United States; The ...

.

Background

Emergence of Solidarity in Poland

Labour turmoil in Poland during 1980 led to the formation of the independent

trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

Solidarity, led by

Lech Wałęsa

Lech Wałęsa (; ; born 29 September 1943) is a Polish statesman, dissident, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, who served as the President of Poland between 1990 and 1995. After winning the 1990 election, Wałęsa became the first democratica ...

, which over time became a political force, nevertheless, on 13 December 1981, Polish Prime Minister

Wojciech Jaruzelski

Wojciech Witold Jaruzelski (; 6 July 1923 – 25 May 2014) was a Polish military officer, politician and ''de facto'' leader of the Polish People's Republic from 1981 until 1989. He was the First Secretary of the Polish United Workers' Party b ...

started a crackdown on Solidarity by declaring

martial law in Poland, suspending the union, and temporarily imprisoning all of its leaders.

Mikhail Gorbachev

Although several Eastern Bloc countries had attempted some abortive, limited economic and political reform since the 1950s (e.g. the

Hungarian Revolution of 1956

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 (23 October – 10 November 1956; hu, 1956-os forradalom), also known as the Hungarian Uprising, was a countrywide revolution against the government of the Hungarian People's Republic (1949–1989) and the Hunga ...

and

Prague Spring

The Prague Spring ( cs, Pražské jaro, sk, Pražská jar) was a period of political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected First Sec ...

of 1968), the ascension of reform-minded Soviet leader

Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

in 1985 signaled the trend toward greater liberalization. During the mid-1980s, a younger generation of Soviet

apparatchiks

__NOTOC__

An apparatchik (; russian: аппара́тчик ) was a full-time, professional functionary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union or the Soviet government ''apparat'' ( аппарат, apparatus), someone who held any positio ...

, led by Gorbachev, began advocating fundamental reform in order to reverse years of

Brezhnev stagnation

The "Era of Stagnation" (russian: Пери́од засто́я, Períod zastóya, or ) is a term coined by Mikhail Gorbachev in order to describe the negative way in which he viewed the economic, political, and social policies of the Soviet Uni ...

. After decades of growth, the Soviet Union was now facing a period of severe economic decline and needed Western technology and credits to make up for its increasing backwardness. The costs of maintaining its military, the

KGB

The KGB (russian: links=no, lit=Committee for State Security, Комитет государственной безопасности (КГБ), a=ru-KGB.ogg, p=kəmʲɪˈtʲet ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)əj bʲɪzɐˈpasnəsʲtʲɪ, Komitet gosud ...

, and subsidies to foreign client states further strained the moribund

Soviet economy

The economy of the Soviet Union was based on state ownership of the means of production, collective farming, and industrial manufacturing. An administrative-command system managed a distinctive form of central planning. The Soviet economy was ...

.

Mikhail Gorbachev succeeded to the

General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED O ...

and came to power in 1985. The first signs of major reform came in 1986 when Gorbachev launched a policy of ''

glasnost

''Glasnost'' (; russian: link=no, гласность, ) has several general and specific meanings – a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information, the inadmissibility of hushing up problems, ...

'' (openness) in the Soviet Union, and emphasized the need for ''

perestroika

''Perestroika'' (; russian: links=no, перестройка, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg) was a political movement for reform within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s widely associated wit ...

'' (economic restructuring). By the spring of 1989, the Soviet Union had not only experienced lively media debate but had also held its first multi-candidate elections in the newly established

Congress of People's Deputies. While glasnost ostensibly advocated openness and political criticism, these were only permitted within a narrow spectrum dictated by the state. The general public in the Eastern Bloc was still subject to

secret police

Secret police (or political police) are intelligence, security or police agencies that engage in covert operations against a government's political, religious, or social opponents and dissidents. Secret police organizations are characteristic of a ...

and

political repression

Political repression is the act of a state entity controlling a citizenry by force for political reasons, particularly for the purpose of restricting or preventing the citizenry's ability to take part in the political life of a society, thereb ...

.

Gorbachev urged his Central and Southeast European counterparts to imitate ''perestroika'' and ''glasnost'' in their own countries. However, while reformists in Hungary and Poland were emboldened by the force of liberalization spreading from the east, other Eastern Bloc countries remained openly skeptical and demonstrated aversion to reform. Believing Gorbachev's reform initiatives would be short-lived, hardline communist rulers like

East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

's

Erich Honecker

Erich Ernst Paul Honecker (; 25 August 1912 – 29 May 1994) was a German communist politician who led the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) from 1971 until shortly before the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. He held the posts ...

,

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

's

Todor Zhivkov

Todor Hristov Zhivkov ( bg, Тодор Христов Живков ; 7 September 1911 – 5 August 1998) was a Bulgarian communist statesman who served as the ''de facto'' leader of the People's Republic of Bulgaria (PRB) from 1954 until 1989 ...

,

Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

's

Gustáv Husák

Gustáv Husák (, , ; 10 January 1913 – 18 November 1991) was a Czechoslovak communist politician of Slovak origin, who served as the long-time First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia from 1969 to 1987 and the president o ...

and

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

's

Nicolae Ceaușescu

Nicolae Ceaușescu ( , ; – 25 December 1989) was a Romanian communist politician and dictator. He was the general secretary of the Romanian Communist Party from 1965 to 1989, and the second and last Communist leader of Romania. He was ...

obstinately ignored the calls for change. "When your neighbor puts up new wallpaper, it doesn't mean you have to too," declared one East German

politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the executive committee for communist parties. It is present in most former and existing communist states.

Names

The term "politburo" in English comes from the Russian ''Politbyuro'' (), itself a contraction ...

member.

[.]

Soviet republics

By the late 1980s, people in the

Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historically ...

and

Baltic states

The Baltic states, et, Balti riigid or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term, which currently is used to group three countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, ...

were demanding more autonomy from

Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

, and the Kremlin was losing some of its control over certain regions and elements in the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. Cracks in the Soviet system had begun in December 1986 in

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

when its citizens

protested over an ethnic Russian who had been appointed as the secretary of the

CPSU's Kazakh republican branch. These protests were put down after three days.

In November 1988, the

Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Estonian SSR,, russian: Эстонская ССР officially the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic,, russian: Эстонская Советская Социалистическая Республика was an ethnically based adminis ...

issued a

declaration of sovereignty, which would eventually lead to other states making similar declarations of autonomy.

The

Chernobyl disaster

The Chernobyl disaster was a nuclear accident that occurred on 26 April 1986 at the No. 4 reactor in the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, near the city of Pripyat in the north of the Ukrainian SSR in the Soviet Union. It is one of only two nuc ...

in April 1986 had major political and social effects that catalyzed or at least partially caused the Revolutions of 1989. One political result of the disaster was the greatly increased significance of the new Soviet policy of glasnost.

It is difficult to establish the total economic cost of the disaster. According to Gorbachev, the Soviet Union spent 18 billion

roubles

The ruble (American English) or rouble (Commonwealth English) (; rus, рубль, p=rublʲ) is the currency unit of Belarus and Russia. Historically, it was the currency of the Russian Empire and of the Soviet Union.

, currencies named ''rub ...

(the equivalent of US$18 billion at that time) on containment and decontamination, virtually bankrupting itself.

[Gorbachev, Mikhail (1996), interview in Johnson, Thomas, ', ]ilm Ilm or ILM may refer to:

Acronyms

* Identity Lifecycle Manager, a Microsoft Server Product

* '' I Love Money,'' a TV show on VH1

* Independent Loading Mechanism, a mounting system for CPU sockets

* Industrial Light & Magic, an American motion ...

Discovery Channel, retrieved 19 February 2014.

Impact of Solidarity grows

Throughout the mid-1980s,

Solidarity persisted solely as an underground organization, supported by the Catholic Church. However, by the late 1980s, Solidarity became sufficiently strong to frustrate

Jaruzelski's attempts at reform, and

nationwide strikes in 1988 forced the government to open dialogue with Solidarity. On 9 March 1989, both sides agreed to a

bicameral legislature called the

National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the rep ...

. The already existing

Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of t ...

would become the lower house. The Senate would be elected by the people. Traditionally a ceremonial office, the presidency was given more powers (

Polish Round Table Agreement

The Polish Round Table Talks took place in Warsaw, Poland from 6 February to 5 April 1989. The government initiated talks with the banned trade union Solidarność and other opposition groups in an attempt to defuse growing social unrest.

Histo ...

).

On 7 July 1989, General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev implicitly renounced the use of force against other Soviet-bloc nations. Speaking to members of the 23-nation Council of Europe, Mr. Gorbachev made no direct reference to the so-called

Brezhnev Doctrine

The Brezhnev Doctrine was a Soviet foreign policy that proclaimed any threat to socialist rule in any state of the Soviet Bloc in Central and Eastern Europe was a threat to them all, and therefore justified the intervention of fellow socialist st ...

, under which Moscow had asserted the right to use force to prevent a Warsaw Pact member from leaving the communist fold. He stated, "Any interference in domestic affairs and any attempts to restrict the sovereignty of states—friends, allies or any others—are inadmissible". The policy was termed the

Sinatra Doctrine

The Sinatra Doctrine was a Soviet foreign policy under Mikhail Gorbachev for allowing member states of the Warsaw Pact to determine their own internal affairs. The name jokingly alluded to the song My Way popularized by Frank Sinatra—the So ...

, in a joking reference to the

Frank Sinatra

Francis Albert Sinatra (; December 12, 1915 – May 14, 1998) was an American singer and actor. Nicknamed the "Honorific nicknames in popular music, Chairman of the Board" and later called "Ol' Blue Eyes", Sinatra was one of the most popular ...

song "

My Way

"My Way" is a song popularized in 1969 by Frank Sinatra set to the music of the French song "Comme d'habitude" composed by Jacques Revaux with lyrics by Gilles Thibaut and Claude François and first performed in 1967 by Claude François. Its E ...

". Poland became the first Warsaw Pact country to break free of Soviet domination.

Fall of dictatorial regimes

In February 1986, in one of the first peaceful, mass-

movement revolutions against a

dictatorship

A dictatorship is a form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, which holds governmental powers with few to no limitations on them. The leader of a dictatorship is called a dictator. Politics in a dictatorship are ...

, the

People Power Revolution

The People Power Revolution, also known as the EDSA Revolution or the February Revolution, was a series of popular Demonstration (people), demonstrations in the Philippines, mostly in Metro Manila, from February 22 to 25, 1986. There was a ...

in the

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

peacefully overthrew dictator

Ferdinand Marcos

Ferdinand Emmanuel Edralin Marcos Sr. ( , , ; September 11, 1917 – September 28, 1989) was a Filipino politician, lawyer, dictator, and kleptocrat who was the 10th president of the Philippines from 1965 to 1986. He ruled under martial ...

and inaugurated

Cory Aquino

Maria Corazon "Cory" Sumulong Cojuangco-Aquino (; ; January 25, 1933 – August 1, 2009) was a Filipina politician who served as the 11th president of the Philippines from 1986 to 1992. She was the most prominent figure of the 1986 People P ...

as the

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

.

The

domino effect

A domino effect or chain reaction is the cumulative effect generated when a particular event triggers a chain of similar events. This term is best known as a mechanical effect and is used as an analogy to a falling row of dominoes. It typically ...

of the revolutions of 1989 affected other regimes as well. The

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

n

apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

regime and

Pinochet's military dictatorship in Chile were gradually dismantled during the 1990s as the West withdrew their funding and diplomatic support.

Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

,

Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

,

Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the cou ...

,

South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and sharing a Korean Demilitarized Zone, land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed ...

,

Suriname

Suriname (; srn, Sranankondre or ), officially the Republic of Suriname ( nl, Republiek Suriname , srn, Ripolik fu Sranan), is a country on the northeastern Atlantic coast of South America. It is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north ...

,

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

and

North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

-

South Yemen, among many others, elected democratic governments.

Exact tallies of the number of democracies vary depending on the criteria used for assessment, but by some measures by the late 1990s there were well over 100 democracies in the world, a marked increase in just a few decades.

National political movements

Poland

A

wave of strikes hit Poland from 21 April then this continued in May 1988. A second wave began on 15 August, when a strike broke out at the

July Manifesto coal mine in

Jastrzębie-Zdrój

Jastrzębie-Zdrój (; german: Bad Königsdorff-Jastrzemb, originally ''Jastrzemb'', cs, Lázně Jestřebí, szl, Jastrzymbie-Zdrōj or ''Jastrzymbje-Zdrůj'') is a city in south Poland with 86,632 inhabitants (2021). Its name comes from the Poli ...

, with the workers demanding the re-legalisation of the Solidarity trade union. Over the next few days, sixteen other mines went on strike followed by a number of shipyards, including on 22 August the

Gdansk Shipyard, famous as the epicentre of the

1980 industrial unrest that spawned Solidarity. On 31 August 1988

Lech Wałęsa

Lech Wałęsa (; ; born 29 September 1943) is a Polish statesman, dissident, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, who served as the President of Poland between 1990 and 1995. After winning the 1990 election, Wałęsa became the first democratica ...

, the leader of Solidarity, was invited to Warsaw by the communist authorities, who had finally agreed to talks.

On 18 January 1989 at a stormy session of the Tenth Plenary Session of the ruling

United Workers' Party, General

Wojciech Jaruzelski

Wojciech Witold Jaruzelski (; 6 July 1923 – 25 May 2014) was a Polish military officer, politician and ''de facto'' leader of the Polish People's Republic from 1981 until 1989. He was the First Secretary of the Polish United Workers' Party b ...

, the First Secretary, managed to get party backing for formal negotiations with Solidarity leading to its future legalisation, although this was achieved only by threatening the resignation of the entire party leadership if thwarted. On 6 February 1989 formal Round Table discussions began in the Hall of Columns in Warsaw. On 4 April 1989 the historic

Round Table Agreement was signed legalising Solidarity and setting up partly free

parliamentary elections

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

to be held on 4 June 1989 (incidentally, the day following the midnight crackdown on Chinese protesters in Tiananmen Square). A political earthquake followed as the victory of Solidarity surpassed all predictions. Solidarity candidates captured all the seats they were allowed to compete for in the

Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of t ...

, while in the

Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

they captured 99 out of the 100 available seats (with the one remaining seat taken by an independent candidate). At the same time, many prominent communist candidates failed to gain even the minimum number of votes required to capture the seats that were reserved for them.

On 15 August 1989, the communists' two longtime coalition partners, the

United People's Party (ZSL) and the

Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

(SD), broke their alliance with the PZPR and announced their support for Solidarity. The last communist Prime Minister of Poland, General

Czesław Kiszczak

Czesław Jan Kiszczak (19 October 1925 – 5 November 2015) was a Polish general, communist-era interior minister (1981–1990) and prime minister (1989).

In 1981 he played a key role in imposing martial law and suppression of the '' Solidar ...

, said he would resign to allow a non-communist to form an administration. As Solidarity was the only other political grouping that could possibly form a government, it was virtually assured that a Solidarity member would become prime minister. On 19 August 1989, in a stunning watershed moment,

Tadeusz Mazowiecki

Tadeusz Mazowiecki (; 18 April 1927 – 28 October 2013) was a Polish author, journalist, philanthropist and Christian-democratic politician, formerly one of the leaders of the Solidarity movement, and the first non-communist Polish prime min ...

, an anti-communist editor, Solidarity supporter, and devout Catholic, was nominated as Prime Minister of Poland and the Soviet Union voiced no protest. Five days later, on 24 August 1989, Poland's Parliament ended more than 40 years of one-party rule by making Mazowiecki the country's first non-communist Prime Minister since the early postwar years. In a tense Parliament, Mazowiecki received 378 votes, with 4 against and 41 abstentions. On 13 September 1989, a new non-communist government was approved by parliament, the first of its kind in the

Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

. On 17 November 1989 the statue of

Felix Dzerzhinsky

Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky ( pl, Feliks Dzierżyński ; russian: Фе́ликс Эдму́ндович Дзержи́нский; – 20 July 1926), nicknamed "Iron Felix", was a Bolshevik revolutionary and official, born into Poland, Polish n ...

, Polish founder of the

Cheka

The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission ( rus, Всероссийская чрезвычайная комиссия, r=Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya, p=fsʲɪrɐˈsʲijskəjə tɕrʲɪzvɨˈtɕæjnəjə kɐˈmʲisʲɪjə), abbreviated ...

and symbol of communist oppression, was torn down in

Bank Square, Warsaw

Plac Bankowy ( en, 'Bank Square', formerly ''Plac Dzierżyńskiego'') is one of Warsaw's principal squares. Located in the downtown district, adjacent to the Saxon Garden and Warsaw Arsenal, it is also a principal public-transport hub, with bu ...

. On 29 December 1989 the Sejm amended the constitution to change the official name of the country from the People's Republic of Poland to the Republic of Poland. The communist Polish United Workers' Party dissolved itself on 29 January 1990 and transformed itself into the

Social Democracy of the Republic of Poland

Social Democracy of the Republic of Poland (SdRP) ( pl, Socjaldemokracja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, SdRP) was a social-democratic political party in Poland created in 1990, shortly after the Revolutions of 1989. The party was the main party of ...

.

In 1990, Jaruzelski resigned as Poland's president and was succeeded by Wałęsa, who won the

1990 presidential elections[.] held in two rounds on 25 November and 9 December. Wałęsa's inauguration as president on 21 December 1990 is considered by many as the formal end of the communist

People's Republic of Poland

The Polish People's Republic ( pl, Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, PRL) was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern Republic of Poland. With a population of approximately 37.9 million nea ...

and the start of the modern

Republic of Poland. The

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republic ...

was dissolved on 1 July 1991. On 27 October 1991 the

first entirely free Polish parliamentary elections since 1945 took place. This completed Poland's transition from communist Party rule to a Western-style liberal democratic political system. The last Russian troops left Poland on 18 September 1993.

Hungary

Following Poland's lead, Hungary was next to switch to a non-communist government. Although Hungary had achieved some lasting economic reforms and limited political liberalization during the 1980s, major reforms only occurred following the replacement of

János Kádár

János József Kádár (; ; 26 May 1912 – 6 July 1989), born János József Czermanik, was a Hungarian communist leader and the General Secretary of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party, a position he held for 32 years. Declining health le ...

as General Secretary of the communist Party on 23 May 1988 with

Károly Grósz. On 24 November 1988

Miklós Németh

Miklós Németh (, born 24 January 1948) is a retired Hungarian economist and politician who served as Prime Minister of Hungary from 24 November 1988 to 23 May 1990. He was one of the leaders of the Socialist Workers' Party, Hungary's Communi ...

was appointed Prime Minister. On 12 January 1989, the Parliament adopted a "democracy package", which included trade union pluralism; freedom of association, assembly, and the press; a new electoral law; and a radical revision of the constitution, among other provisions. On 29 January 1989, contradicting the official view of history held for more than 30 years, a member of the ruling Politburo,

Imre Pozsgay

Imre András Pozsgay (''Pozsgay Imre'', ; 26 November 1933 – 25 March 2016) was a Hungarian Communist politician who played a key role in Hungary's transition to democracy after 1988. He served as Minister of Culture (1976–1980), Minister ...

, declared that Hungary's 1956 rebellion was a popular uprising rather than a foreign-instigated attempt at counterrevolution.

Mass demonstrations on 15 March, the National Day, persuaded the regime to begin negotiations with the emergent non-communist political forces.

Round Table talks began on 22 April and continued until the Round Table agreement was signed on 18 September. The talks involved the communists (MSzMP) and the newly emerging independent political forces

Fidesz

Fidesz – Hungarian Civic Alliance (; hu, Fidesz – Magyar Polgári Szövetség) is a right-wing populist and national-conservative political party in Hungary, led by Viktor Orbán.

It was formed in 1988 under the name of Alliance of Young ...

, the

Alliance of Free Democrats

The Alliance of Free Democrats – Hungarian Liberal Party ( hu, Szabad Demokraták Szövetsége – a Magyar Liberális Párt, SZDSZ) was a liberal political party in Hungary.

The SZDSZ was a member of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrat ...

(SzDSz), the

Hungarian Democratic Forum

The Hungarian Democratic Forum ( hu, Magyar Demokrata Fórum, MDF) was a centre-right political party in Hungary. It had a Hungarian nationalist, national-conservative, Christian-democratic ideology. The party was represented continuously in the ...

(MDF), the

Independent Smallholders' Party

The Independent Smallholders, Agrarian Workers and Civic Party ( hu, Független Kisgazda-, Földmunkás- és Polgári Párt), known mostly by its acronym FKgP or its shortened form Independent Smallholders' Party ( hu, Független Kisgazdapárt), ...

, the

Hungarian People's Party

The Hungarian People's Party ( ro, Partidul Popular Maghiar, PPM) was a political party in Romania.

History

The party ran in alliance with the National Peasants' Party

The National Peasants' Party (also known as the National Peasant Party or ...

, the Endre Bajcsy-Zsilinszky Society, and the Democratic Trade Union of Scientific Workers. At a later stage the

Democratic Confederation of Free Trade Unions and the

Christian Democratic People's Party (KDNP) were invited. At these talks a number of Hungary's future political leaders emerged, including

László Sólyom

László Sólyom ( hu, Sólyom László, ; born 3 January 1942) is a Hungarian political figure, lawyer, and librarian who was President of Hungary from 2005 until 2010. Previously he was Chief Justice of the Constitutional Court of Hungary f ...

,

József Antall

József Tihamér Antall Jr. ( hu, ifjabb Antall József Tihamér, ; 8 April 1932 – 12 December 1993) was a Hungarian teacher, librarian, historian, and statesman who served as the first democratically elected Prime Minister of Hungary, holdi ...

,

György Szabad, Péter Tölgyessy and

Viktor Orbán

Viktor Mihály Orbán (; born 31 May 1963) is a Hungarian politician who has served as prime minister of Hungary since 2010, previously holding the office from 1998 to 2002. He has presided over Fidesz since 1993, with a brief break between 20 ...

.

On 2 May 1989, the first visible cracks in the

Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. The term symbolizes the efforts by the Soviet Union (USSR) to block itself and its s ...

appeared when

Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

began

dismantling its long border fence with Austria. This increasingly destabilized East Germany and

Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

over the summer and autumn, as thousands of their citizens illegally crossed over to the West through the Hungarian-Austrian border. On 1 June 1989 the Communist Party admitted that former Prime Minister

Imre Nagy

Imre Nagy (; 7 June 1896 – 16 June 1958) was a Hungarian communist politician who served as Chairman of the Council of Ministers (''de facto'' Prime Minister) of the Hungarian People's Republic from 1953 to 1955. In 1956 Nagy became leader ...

, hanged for treason for his role in the 1956 Hungarian uprising, was executed illegally after a show trial. On 16 June 1989 Nagy was given a solemn funeral on Budapest's largest square in front of crowds of at least 100,000, followed by a hero's burial.

The initially inconspicuous opening of a border gate of the Iron Curtain between Austria and Hungary in August 1989 then triggered a chain reaction, at the end of which the GDR no longer existed and the Eastern Bloc had disintegrated. It was the largest escape movement from East Germany since the Berlin Wall was built in 1961. The idea of opening the border came from

Otto von Habsburg

Otto von Habsburg (german: Franz Joseph Otto Robert Maria Anton Karl Max Heinrich Sixtus Xaver Felix Renatus Ludwig Gaetan Pius Ignatius, hu, Ferenc József Ottó Róbert Mária Antal Károly Max Heinrich Sixtus Xaver Felix Renatus Lajos Gaetan ...

and was brought up by him to

Miklós Németh

Miklós Németh (, born 24 January 1948) is a retired Hungarian economist and politician who served as Prime Minister of Hungary from 24 November 1988 to 23 May 1990. He was one of the leaders of the Socialist Workers' Party, Hungary's Communi ...

, who promoted the idea.

[Miklós Németh in Interview, Austrian TV - ORF "Report", 25 June 2019.] The local organization in Sopron took over the Hungarian Democratic Forum, the other contacts were made via Habsburg and

Imre Pozsgay

Imre András Pozsgay (''Pozsgay Imre'', ; 26 November 1933 – 25 March 2016) was a Hungarian Communist politician who played a key role in Hungary's transition to democracy after 1988. He served as Minister of Culture (1976–1980), Minister ...

. Extensive advertising for the planned picnic was made by posters and flyers among the GDR holidaymakers in Hungary. The Austrian branch of the

Paneuropean Union

The International Paneuropean Union, also referred to as the Pan-European Movement and the Pan-Europa Movement, is the oldest European unification movement.

It began with the publishing of Count Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi's manifesto ''P ...

, which was then headed by

Karl von Habsburg

Karl von Habsburg (given names: ''Karl Thomas Robert Maria Franziskus Georg Bahnam''; born 11 January 1961) is an Austrian politician and the head of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, therefore being a claimant to the defunct Austro-Hungarian t ...

, distributed thousands of brochures inviting them to a picnic near the border at Sopron. After the pan-European picnic,

Erich Honecker

Erich Ernst Paul Honecker (; 25 August 1912 – 29 May 1994) was a German communist politician who led the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) from 1971 until shortly before the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. He held the posts ...

dictated the ''Daily Mirror'' of 19 August 1989: "Habsburg distributed leaflets far into Poland, on which the East German holidaymakers were invited to a picnic. When they came to the picnic, they were given gifts, food and Deutsche Mark, and then they were persuaded to come to the West." But with the mass exodus at the Pan-European Picnic, the subsequent hesitant behavior of the Socialist Unity Party of East Germany and the non-intervention of the Soviet Union broke the dams. Now tens of thousands of the media-informed East Germans made their way to Hungary, which was no longer ready to keep its borders completely closed or to oblige its border troops to use force of arms. In particular, the leadership of the GDR in East Berlin no longer dared to completely block the borders of their own country.

[Andreas Rödder, Deutschland einig Vaterland – Die Geschichte der Wiedervereinigung (2009).]

The

Round Table agreement of 18 September encompassed six draft laws that covered an overhaul of the

Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

, establishment of a

Constitutional Court

A constitutional court is a high court that deals primarily with constitutional law. Its main authority is to rule on whether laws that are challenged are in fact unconstitutional, i.e. whether they conflict with constitutionally established ...

, the functioning and management of political parties, multiparty elections for National Assembly deputies, the penal code and the law on penal procedures (the last two changes represented an additional separation of the Party from the state apparatus). The electoral system was a compromise: about half of the deputies would be elected proportionally and half by the majoritarian system. A weak presidency was also agreed upon, but no consensus was attained on who should elect the president (parliament or the people) and when this election should occur (before or after parliamentary elections). On 7 October 1989, the Communist Party at its last congress re-established itself as the

Hungarian Socialist Party. In a historic session from 16 to 20 October, the parliament adopted legislation providing for

a multi-party parliamentary election and a direct presidential election, which took place on 24 March 1990. The legislation transformed Hungary from a

People's Republic

People's republic is an official title, usually used by some currently or formerly communist or left-wing states. It is mainly associated with soviet republics, socialist states following people's democracy, sovereign states with a democratic- ...

into the

Republic of Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the ...

, guaranteed human and civil rights, and created an institutional structure that ensured separation of powers among the judicial, legislative, and executive branches of government. On 23 October 1989, on the 33rd anniversary of the 1956 Revolution, the communist regime in Hungary was formally abolished. The

Soviet military occupation of Hungary, which had persisted since World War II, ended on 19 June 1991.

East Germany

On 2 May 1989,

Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

started dismantling its barbed-wire border with

Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

. The

border

Borders are usually defined as geographical boundaries, imposed either by features such as oceans and terrain, or by political entities such as governments, sovereign states, federated states, and other subnational entities. Political borders c ...

was still heavily guarded, but it was a political sign. The

Pan-European Picnic

The Pan-European Picnic (german: Paneuropäisches Picknick; hu, páneurópai piknik; sk, Paneurópsky piknik) was a peace demonstration held on the Austrian- Hungarian border near Sopron, Hungary on 19 August 1989. The opening of the border ...

in August 1989 finally started a movement that could not be stopped by the rulers in the Eastern Bloc. It was the largest escape movement from East Germany since the Berlin Wall was built in 1961. The patrons of the picnic,

Otto von Habsburg

Otto von Habsburg (german: Franz Joseph Otto Robert Maria Anton Karl Max Heinrich Sixtus Xaver Felix Renatus Ludwig Gaetan Pius Ignatius, hu, Ferenc József Ottó Róbert Mária Antal Károly Max Heinrich Sixtus Xaver Felix Renatus Lajos Gaetan ...

and the Hungarian Minister of State

Imre Pozsgay

Imre András Pozsgay (''Pozsgay Imre'', ; 26 November 1933 – 25 March 2016) was a Hungarian Communist politician who played a key role in Hungary's transition to democracy after 1988. He served as Minister of Culture (1976–1980), Minister ...

saw the planned event as an opportunity to test the reaction of Mikhail Gorbachev and the Eastern Bloc countries to a large opening of the border including flight. After the pan-European picnic, Erich Honecker dictated the Daily Mirror of 19 August 1989: "Habsburg distributed leaflets far into Poland, on which the East German holidaymakers were invited to a picnic. When they came to the picnic, they were given gifts, food, and Deutsche Mark, and then they were persuaded to come to the West." But with the mass exodus at the Pan-European Picnic, the subsequent hesitant behavior of the Socialist Unity Party of East Germany and the non-intervention of the Soviet Union broke the dams. Now tens of thousands of the media-informed East Germans made their way to Hungary, which was no longer ready to keep its borders completely closed or to oblige its border troops to use force of arms.

By the end of September 1989, more than 30,000 East Germans had escaped to the West before the

GDR denied travel to Hungary, leaving

Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

as the only neighboring state to which East Germans could escape. Thousands of East Germans tried to reach the West by occupying the West German diplomatic facilities in other Central and Eastern European capitals, notably the

Prague Embassy

The Embassy of Germany in Prague is located on Vlašská street (formerly ''Wälsche Spitalgasse''), in the Malá Strana district of Prague, Czech Republic.

Since the establishment of diplomatic relations between West Germany and Czechoslovakia i ...

and the Hungarian Embassy, where thousands camped in the muddy garden from August to November waiting for German political reform. The GDR closed the border to Czechoslovakia on 3 October, thereby isolating itself from all its neighbors. Having been shut off from their last chance for escape, an increasing number of East Germans participated in the

Monday demonstrations in Leipzig on 4, 11, and 18 September, each attracting 1,200 to 1,500 demonstrators. Many were arrested and beaten, but the people refused to be intimidated. On 25 September, the protests attracted 8,000 demonstrators.

After the fifth successive Monday demonstration in

Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as wel ...

on 2 October attracted 10,000 protesters,

Socialist Unity Party (SED) leader

Erich Honecker

Erich Ernst Paul Honecker (; 25 August 1912 – 29 May 1994) was a German communist politician who led the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) from 1971 until shortly before the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. He held the posts ...

issued a ''shoot and kill'' order to the military.

Communists prepared a huge police, militia,

Stasi

The Ministry for State Security, commonly known as the (),An abbreviation of . was the Intelligence agency, state security service of the East Germany from 1950 to 1990.

The Stasi's function was similar to the KGB, serving as a means of maint ...

, and work-combat troop presence, and there were rumors a Tiananmen Square-style massacre was being planned for the following Monday's demonstration on 9 October.

On 6 and 7 October,

Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

visited East Germany to mark the 40th anniversary of the German Democratic Republic, and urged the East German leadership to accept reform. A famous quote of his is rendered in German as "Wer zu spät kommt, den bestraft das Leben" ("The one who comes too late is punished by life."). However, Honecker remained opposed to internal reform, with his regime even going so far as forbidding the circulation of Soviet publications that it viewed as subversive.

In spite of rumors that the communists were planning a massacre on 9 October, 70,000 citizens demonstrated in Leipzig that Monday and the authorities on the ground refused to open fire. The following Monday, 16 October 120,000 people demonstrated on the streets of Leipzig.

Erich Honecker had hoped that the

Soviet troops stationed in the GDR by the

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republic ...

would restore the communist government and suppress the civilian protests. By 1989 the Soviet government deemed it impractical for the Soviet Union to

continue asserting its control over the Eastern Bloc, so it took a neutral stance regarding the events happening in East Germany. Soviet troops stationed in eastern Europe were under strict instructions from the Soviet leadership not to intervene in the political affairs of the Eastern Bloc nations and remained in their barracks. Faced with ongoing civil unrest, the SED deposed Honecker on 18 October and replaced him with the number-two-man in the regime,

Egon Krenz

Egon Rudi Ernst Krenz (; born 19 March 1937) is a German former politician who was the last Communist leader of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) during the Revolutions of 1989. He succeeded Erich Honecker as the General Secretary ...

. However, the demonstrations kept growing, and on Monday, 23 October, the Leipzig protesters numbered 300,000 and remained as large the following week.

The border to Czechoslovakia was opened again on 1 November, and the Czechoslovak authorities soon let all East Germans travel directly to West Germany without further bureaucratic ado, thus lifting their part of the Iron Curtain on 3 November. On 4 November the authorities decided to authorize a demonstration in Berlin and were faced with the

Alexanderplatz demonstration

The Alexanderplatz demonstration (german: link=no, Alexanderplatz-Demonstration) was a demonstration for political reforms and against the government of the German Democratic Republic on Alexanderplatz in East Berlin on Saturday 4 November 198 ...

, where half a million citizens converged on the capital demanding freedom in the biggest protest the GDR ever witnessed. Unable to stem the ensuing flow of refugees to the West through Czechoslovakia, the East German authorities eventually caved in to public pressure by allowing East German citizens to enter West Berlin and West Germany directly, via existing border points, on 9 November 1989, without having properly briefed the border guards. Triggered by the erratic words of regime spokesman

Günter Schabowski

Günter Schabowski (; 4 January 1929 – 1 November 2015) was an East German politician who served as an official of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (''Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands'' abbreviated ''SED''), the ruling party du ...

in a TV press conference, stating that the planned changes were in effect "immediately, without delay," hundreds of thousands of people took advantage of the opportunity. The guards were quickly overwhelmed by the growing crowds of people demanding to be let out into West Berlin. After receiving no feedback from their superiors, the guards, unwilling to use force, relented and

opened the gates to West Berlin. Soon new crossing points were forced open in the

Berlin Wall

The Berlin Wall (german: Berliner Mauer, ) was a guarded concrete barrier that encircled West Berlin from 1961 to 1989, separating it from East Berlin and East Germany (GDR). Construction of the Berlin Wall was commenced by the government ...

by the people, and sections of the wall were literally torn down. The guards were unaware of what was happening and stood by as the East Germans took to the wall with hammers and chisels.

On 7 November, the entire ''Ministerrat der DDR'' (

State Council of East Germany

The State Council of East Germany (German: ''Staatsrat der DDR'') was the collective head of state of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) from 1960 to 1990.

Origins

When the German Democratic Republic was founded in October 1949, its ...

), including its chairman

Willi Stoph

Wilhelm Stoph (9 July 1914 – 13 April 1999) was a German politician. He served as Chairman of the Council of Ministers (Prime Minister) of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) from 1964 to 1973, and again from 1976 until 1989. He ...

, resigned. A new government was formed under a considerably more liberal communist,

Hans Modrow

Hans Modrow (; born 27 January 1928) is a German politician best known as the last communist premier of East Germany.

Taking office in the middle of the Peaceful Revolution, he was the ''de facto'' leader of the country for much of the winter ...

.

On 1 December, the

Volkskammer

__NOTOC__

The Volkskammer (, ''People's Chamber'') was the unicameral legislature of the German Democratic Republic (colloquially known as East Germany).

The Volkskammer was initially the lower house of a bicameral legislature. The upper house ...

removed the SED's leading role from the

constitution of the GDR.

On 3 December Krenz resigned as leader of the SED; he resigned as head of state three days later. On 7 December, Round Table talks opened between the SED and other political parties. On 16 December 1989, the SED was dissolved and refounded as the

SED-PDS, abandoning Marxism–Leninism and becoming a mainstream democratic socialist party.

On 15 January 1990, the Stasi's headquarters was stormed by protesters. Modrow became the de facto leader of

East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

until

free elections were held on 18 March 1990—the first

since November 1932. The SED, renamed the

Party of Democratic Socialism, was heavily defeated.

Lothar de Maizière

Lothar de Maizière (; born 2 March 1940) is a German Christian Democratic politician. In 1990, he served as the only premier of the German Democratic Republic to be democratically elected freely and fairly by the people. He was also the last l ...

of the

East German Christian Democratic Union became Prime Minister on 4 April 1990 on a platform of speedy reunification with the West. On 15 March 1990,

a peace treaty was signed between the two countries of Germany and the four Allies to replace the

Potsdam Agreement of 1 August 1945 after

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...